Battle of Bunker Hill

-

Edit

First major battle of the revolutionary war Breed's Hill

Charlestown, MA

- Phone number

- Business website

Recommended Reviews

-

- Gustav III

- Sweden

- 221 friends

- 564 reviews

- Elite ’16

7/30/1775

I don’t understand why all the Brits here are giving the Battle of Bunker Hill 1 and 2 star reviews. They won, right? And the colonists lost, and they had to give up the whole peninsula to the British, but they’re leaving positive reviews? This makes no sense to me.

I give the battle 4 stars, because after all, it was the first major battle of the American Revolution (Britannica). Lexington and Concord were merely skirmishes, while Bunker Hill was an all-out battle, with strategizing and huge casualties on both sides. I subtract one star for the underwhelming British performance. They shouldn’t have lost so many soldiers to a fledgling, unproven rebel army! -

- Nathaniel Greene

- Colonial general

- 1 friend

- 5 reviews

6/20/1775

Yes we lost, but we cut their army in half!

Ah, Bunker Hill. I recall saying just afterwards, “I wish we could sell them another hill at the same price!” (Fleming 314). The price, in this case, being the thousand or so casualties they lost to us (Britannica).

It all started in 1775, during the Siege of Boston. We had the British in Boston surrounded, so they couldn’t receive food or supplies, so naturally they wanted to break the siege (Fleming 11). When we heard that a British force was about to occupy Dorchester Heights, a strategic high point above Boston from which they could attack our army’s headquarters, we decided to quickly fortify all the surrounding hills (Britannica). Bunker Hill is one of these strategic high points overlooking Boston. The defenders hurriedly dug and piled up earth on top of the hill to form defensive walls (Fleming 27).

The battle began on June 17 (Britannica). Yes, there were some blunders on our side, but I think we put up an excellent fight. Looking back on the situation later, we realized that we had entrenched ourselves on the wrong hill; we were instructed to defend Bunker Hill, but due to the infuriating sameness of the terrain in these parts, wound up defending Breed’s Hill (Britannica). Yet for some reason, they still choose to call it the Battle of Bunker Hill.

The British fired on us from their ships in the river, and from cannons on the opposite bank (Britannica). We in turn had soldiers in the village of Charles-Town, at the south of the peninsula, who were in a perfect position to shoot at the enemy’s left flank as they advanced up Breed’s Hill (Burgoyne).

I gave this battle four stars because of the casualties: we, with our scrappy force of a thousand on the hill, lost 450 men; that’s no cause for celebration, but we picked off 1,000 British soldiers, nearly half their attacking force (Britannica)! The British think they have the world’s best fighting force, but we made them think again! -

- John Burgoyne

- English general

- 1 friend

- 2 reviews

7/1/1775

Far too many British casualties

In the end, we were victorious, and we did drive out the Americans for a time, but the losses we sustained were sobering. Over a thousand men killed or injured, including an uncommon number of officers (Burgoyne). There was no serious possibility of defeat for us, though; we had ships in the river firing on the rebels, we had set fire to Charles-Town where the rebels were shooting from (so they would have had to flee their cover), and we still have the most powerful, disciplined and organized military in the world.

Many are calling the Battle of Bunker Hill a “Pyrrhic Victory” for us. That term refers to a victory that was very damaging to the victor, and gets its name from the ancient Greek king Pyrrhus of Epirus, who lost 7,500 of his best men in just two battles against the Romans. He won both, but, like the British, that fact didn’t make up for the men and morale he lost. -

- John Waller

- English witness

- 22 friends

- 33 reviews

7/12/1775

We were unfamiliar with the terrain and not swift enough

It was as if the land fought on the side of the colonists. Although the rebels had created a “formidable” redoubt on their hill (Waller), we thought we could boldly march up the grassy meadow ahead of us without much trouble. But as it turned out, the slope was treacherously laced with rail fences, hedges, and stone walls, so that our men had to slow down significantly in order to clamber over them. When they were thus exposed, they were shot at from the hill above and from Charlestown to the left (Waller).

We could have perhaps recovered from the confusion the obstacles caused, had we not waited ten or fifteen minutes afterward at the base of the hill while our companies arranged themselves again. I kept insisting we advance immediately, since the rebels were firing at us constantly and decimating our numbers (Waller). If we had marched on the redoubt sooner, I believe we would have had far fewer casualties. Eventually we advanced on the rebels.

I’ll paste an excerpt of one of my letters here, which perfectly captures the scene inside:

"I cannot pretend to describe the Horror of the Scene within the Redoubt, when we enter'd it, 'twas streaming with Blood & strew'd with dead & dying Men the Soldiers stabbing some and dashing out the Brains of other was a sight too dreadful for me to dwell any longer on” (Waller)

This battle “has been very fatal to the 1st Battalion of Marines” and I hope that the rest of our victories against the colonists do not incur casualties in such numbers (Waller). All in all it was an awful day. One star. -

- William Prescott

- Colonial Colonel

- 1 friend

- 4 reviews

6/29/1775

Morale is high despite our retreat, while the enemy's confidence is shattered

When the enemy landed on the peninsula, I dispatched most of my men to flank them, and attack from the side of their army, keeping only 150 with me to guard our position on the hill (Prescott). Three columns of British soldiers advanced on the fort; there were so many of them that we nearly ran out of ammunition, and decided to stop shooting. We waited until they were within 30 yards of the fort, and then “gave them such a hot fire that they were obliged to [retreat] nearly 150 yards” (Prescott). But eventually we were no match for them, and they rallied again and forced their way into the fort with their bayonets. We, with our 150 men, had managed to defend our fort against the strength of the British for an hour and twenty minutes (Prescott).

Morale among our men was high, as it should be! We had held our own against the British and halved their attacking force while sustaining far fewer casualties ourselves (Britannica). These high spirits were soon channeled into fortifying more defenses (Fleming 315). Meanwhile, the tactics of one of the enemy’s major generals, William Howe, have shifted to hesitation and caution after this brutal battle, and so he has let us slip past him several times when he could have attacked us (Fleming 316). -

- William Howe

- English major general

- 0 friends

- 15 reviews

7/5/1775

Too much confidence in ourselves

It seems that the most demoralizing aspect of this battle, and what caused me to deduct three stars, was how our expectations of swift victory were utterly shattered. Let me explain our plan, and then continue to what went wrong.

Fifteen thousand colonists had besieged the British in Boston (Fleming 11). Our people were running out of food because we could not break the siege to resupply them. And a great empire such as Great Britain “does not talk peace without first proving [it] can win the war” (Fleming 17). We had to break the siege by force to prove to them that they could never hope to resist us.

The American army was headquartered in Cambridge. That town would be the weak link which, if broken, would cause the rest of the American army to “evaporate into the woods from whence it came” (Fleming 18). So 1,500 men would land at Dorchester Point and secure the heights on a peninsula above Boston (Fleming 18), and another 2,300 men would secure the heights above Charles-Town, which also overlooks Boston (Britannica). From these two advantageous points the armies could advance downward to attack Cambridge.

To demonstrate our power as an army, it was crucial “to end this embarrassing siege of Boston as quickly as possible” (Fleming 17). That did not happen. The defenders managed to hold us off, killing hundreds upon hundreds of our soldiers, until they finally ran out of ammunition.

As one of our officers said, “Too great a confidence in ourselves which is always dangerous occasioned this dreadful loss… The brave men’s lives were wantonly thrown away” (Fleming 317). In a letter to my brother, I told him, “the success is too dearly bought” (Fleming 315). Possibly if we were more cautious and less overconfident, we could have had a cleaner victory. -

- Benjamin Franklin

- Colonist

- 1 friend

- 38 reviews

7/27/1775

Proof of British oppression, hope for victory

I think the Battle of Bunker Hill proved the lengths the British will go to to maintain their oppression over us. As I said to an old friend, a Mr. Strahan of London, “Look upon your Hands! They are stained with the Blood of your Relations! You and I were long Friends. You are now my Enemy” (Fleming 328). The war has only just begun, and this battle has given us hope. If we can sell every hill and field to the British at this price, they may be left with no soldiers to fight us! Now that our army has finally been tested in a true battle, we have some sense of our abilities. We have not had anywhere near as much fighting experience as the British, but that seems to have no importance. With a better trained army, under the leadership of General George Washington, I give our country a fighting chance. -

- Taite Clark

- Sharon, VT

- 19 friends

- 141 reviews

10/13/2016

The Battle of Bunker Hill is a compelling counterargument to our binary idea of winning and losing. If the Americans “lost” the battle, yet came away with higher morale, and the British “won” but spent months ruminating over what went wrong, what do winning and losing really matter? We judge the side who forces the other to surrender to be the “winner” of a battle, regardless of the damage caused to them. This loses a lot of its meaning in the context of a war, in this case the American Revolutionary War, where overall troop numbers, morale, and positioning matter far more than who happens to control one little hill.

The obvious lesson we can learn from Bunker Hill is that winning is not always worth it. Later in its history, the United States went to war in Vietnam, and in its pursuit of a simple geopolitical victory it turned a generation of its citizens into pacifists who would oppose all future military interventions. And in our series of wars in the Middle East, we have declared victory many times but made ourselves too many enemies for those victories to matter. We ought to reconsider how important military victories are to us, after seeing the outcomes these victories have had.

And of course, Works Cited:

Andrews, Evan. “5 Famous Pyrrhic Victories.” History. A&E Television Networks, 1 September 2015. Web. 9 October 2016. http://www.history.com/news/history-lists/5-famous-pyrrhic-victories

Burgoyne, John. “Letter from John Burgoyne to Lord Stanley.” Massachusetts Historical Society. 25 June 1775. Web 2 Oct. 2016. http://www.masshist.org/bh/burgoynep1text.html

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. “Battle of Bunker Hill.” Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, 12 Aug. 2016. Web. 26 Sep. 2016. https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Bunker-Hill

Fleming, Thomas. The Story of Bunker Hill. Collier Books, 1962.

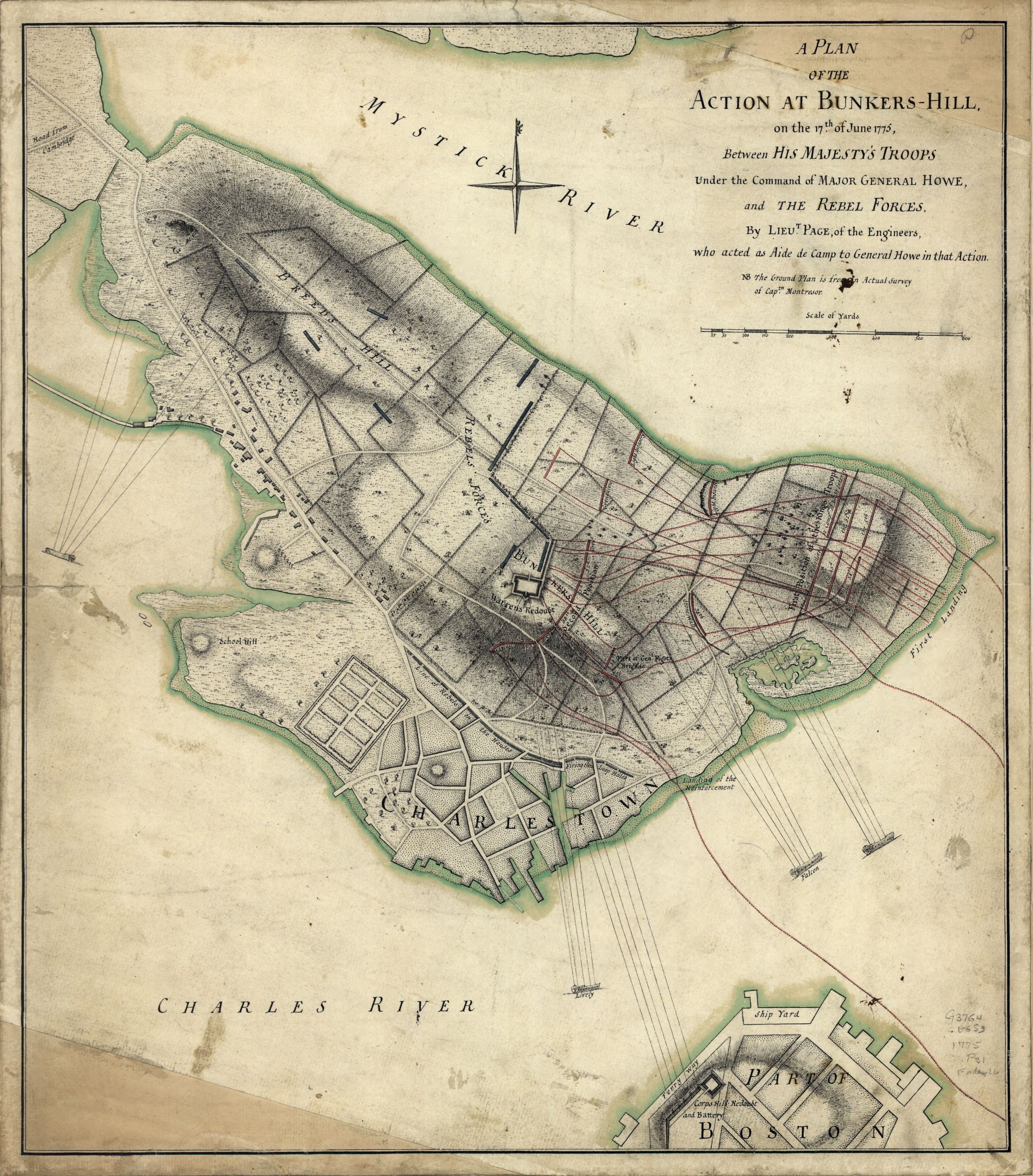

Page, Thomas, and John Montrésor. “A plan of the action at Bunkers-Hill, on the 17th of June, 1775, between His Majesty’s troops under the command of Major General Howe, and the rebel forces.” 1775, map, pen-and-ink and watercolor, Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, DC. https://www.loc.gov/item/gm71000613

Prescott, William. “To John Adams from William Prescott, 25 August 1775.” National Archives. 25 Aug. 1775. Web. 2 Oct. 2016. http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-03-02-0070#PJA03d075n2

Rosiecki, Casimer. “Fields of Deception: The Bunker Hill Battlefield.” National Park Service. U.S. Dept. of the Interior, 2016. Web. 26 Sept. 2016. https://www.nps.gov/bost/learn/historyculture/bunker-hill-battlefield.htm

“Today in History - June 17: The Battle of Bunker Hill.” Library of Congress. Library of Congress, n.d. Web. 26 Sep. 2016. https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/june-17

Waller, John. “Letter from J. Waller to unidentified recipient.” Massachusetts Historical Society. 21 June 1775. Web. 26 Sep. 2016. http://masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=726&img_step=1&mode=transcript#page1

Business info summary

-

$$$$$$$$

- Price range

- Splurge

More business info

-

- Take-out

- No

- Accepts Credit Cards

- No

- Accepts Apple Pay

- No

- Bike Parking

- No

- Wheelchair Accessible

- No

- Good for Kids

- God no

Note from Taite:

If you click anything on this website except for the

photos at the top it will most likely break, since it is a regular Yelp

web page with the guts ripped out and rearranged. Thanks for your

understanding.

Picture sources:

Gustav III: Flickr

Nathaniel Greene: nathanaelgreenehomestead.org

John Burgoyne: nam.ac.uk

William Prescott: Wikimedia

William Howe: reinsteinrevolutionper2.wikispaces.com

Ben Franklin: fretshirt.com

Battle of Lexington: totallyhistory.com

Battle of Yorktown: Wikimedia

Pyrrhus: Wikimedia

Specialties

Greenhearts Family Farm has emerged as the Bay Area's most

loved and highly recommended CSA home delivery service for fresh

organics. Why? Because we are organic farmers first and foremost with a

lifelong connection to the best local organic farmers.

We take

an intensely personal approach to feeding you and your family only what

we grow and eat ourselves. And our farm is a place you'll take great

pride in visiting and calling your own!

We offer the ultimate in farm fresh, organic, pasture raised meats and eggs and artisan produce delivered right to your door.

Greenhearts

is not looking for customers! We are seeking community partners - folks

who want to be part of our farm's CSA, through the successes and

failures, in good times and bad.

So join us at the farmer's table. Eat like you're an organic farmer- fresh, ripe, beautiful, pasture raised, real!

Greenhearts Family Farm CSA - Your Local Farmer's Market Delivered!

History

Established in 2007.

Farmers Paul and Aurora fell in love while working on

organic farms across the globe. They soon started their own business

growing and selling organic produce and pasture raised eggs and chickens

at farmer's markets across the Bay Area and delivering their beautiful

veggie boxes to a handful of neighbors.

The popularity of

Greenhearts Family Farm quickly grew, and it wasn't long before the two

young farmers expanded their farming venture, hiring an amazing crew to

help grow more food and deliver across the Bay Area.

Having

studied and lived with organic pioneers and farm families across the

world, inheriting the honored traditions and methods of natural farming,

Greenhearts Family Farm is a work of art and an act of love, never

simply a business.

Paul & Aurora have dedicated their lives

to community supported organic agriculture. Get to know them personally

when you visit their spectacular Half Moon Bay farm and begin receiving

their beloved CSA box!

Meet the Business Owner

Raised in the middle of an orchard, Paul's first job was on

the farm, spending hot summer days working the apricot harvest. Aurora's

love of the natural world led her from San Francisco to the University

of California Santa Cruz where she earned her Environmental Science

degree.

Having raised many thousands of cage free, organic

chickens on pasture, and grown countless crops, these two farmers spend

every day in the field and at market, gaining keen insight into customer

needs and dynamic trends in sustainable, organic agriculture.

,

,  and related marks are registered trademarks of Yelp.

and related marks are registered trademarks of Yelp.